The Italian rivers took a bit of figuring out...

Nearly 20 years ago, I met Gabe from Berridale, a town on the edge of the Snowy Mountains and close to Lake Eucumbene. He was in the process of buying the Berridale pub from another local personality, Rod Smith. Gabe is a first-generation Italian immigrant who came to Australia as a small boy with his parents in the 1950s. His dad came to work on the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

Gabe’s a larger-than-life character with a reputation for generosity and kindness, for not suffering fools gladly, for his pasta and pizza, late nights, and good wine, grappa and limoncello. He’s not a flyfisher but a lot of his friends are, and an ephemeral Monaro stream stocked with trout by the Monaro Acclimatisation Society, runs through his farm.

Background

Some years ago, Gabe acquired a family home in Possagno, 50 kilometres northwest of Venice. This modest three storey terrace house nestles between four others, all owned by members of his family, right in the foothills of the Dolomite Mountains. Gabe loves hosting his friends from Australia and he has regularly issued me an invitation. If your geography’s a bit rusty, the Dolomites in Italy share a border with Austria to the north and cover 16,000 square kilometres, with some peaks over 3,000 metres. (For comparison, the Kosciuszko National Park covers 6,900 square kilometres, with a high point at Mt Kosciuszko of 2,228 metres.)

Even the foothills of the Dolomites are dramatic.

If your history is up to scratch, you’d know the Italians and the Austrians were in conflict for many years before and during World War 1. Italy was claiming Italian-speaking territory within the Austrian border, whilst Austria, aligned with Hungary, sought to gain territory from Italy based on historic land claims. The resulting conflict and wars led to Italy entering World War 1 and siding with the allied forces. Eventually, the disputed territories were gained by the Italians. By the time the war ended, over 40,000 people had lost their lives on the slopes of the mountains. Many were interred in the Mount Grappa war memorial – visible from Gabe’s house. The memorial is 1776 metres above sea level; Possagno is at 276 metres. It’s impressive.

Planning

Finally, 2025 presented me with an opportunity to take advantage of Gabe’s hospitality. As I was staying in Cornwall for the northern summer, I was able to plan a three-week trip to northern Italy: a few days in Venice, some sightseeing in the mountains, and hopefully some fishing. Now, I was aware that Italy is well-known for its flyfishing, and their best competition flyfishers regularly feature high in the world rankings. (I checked: 3rd place in historic gold medal wins; 2nd place in individual gold rankings.)

I love DIY flyfishing trips so set about Google with enthusiasm and optimism. However, after a few attempts, I was a little disappointed and to be honest, confused. First impressions? Not a lot of useful information, mainly associations representing guides, a few booking sites, and a lot of hyperbole. Not much help for a DIY trip!

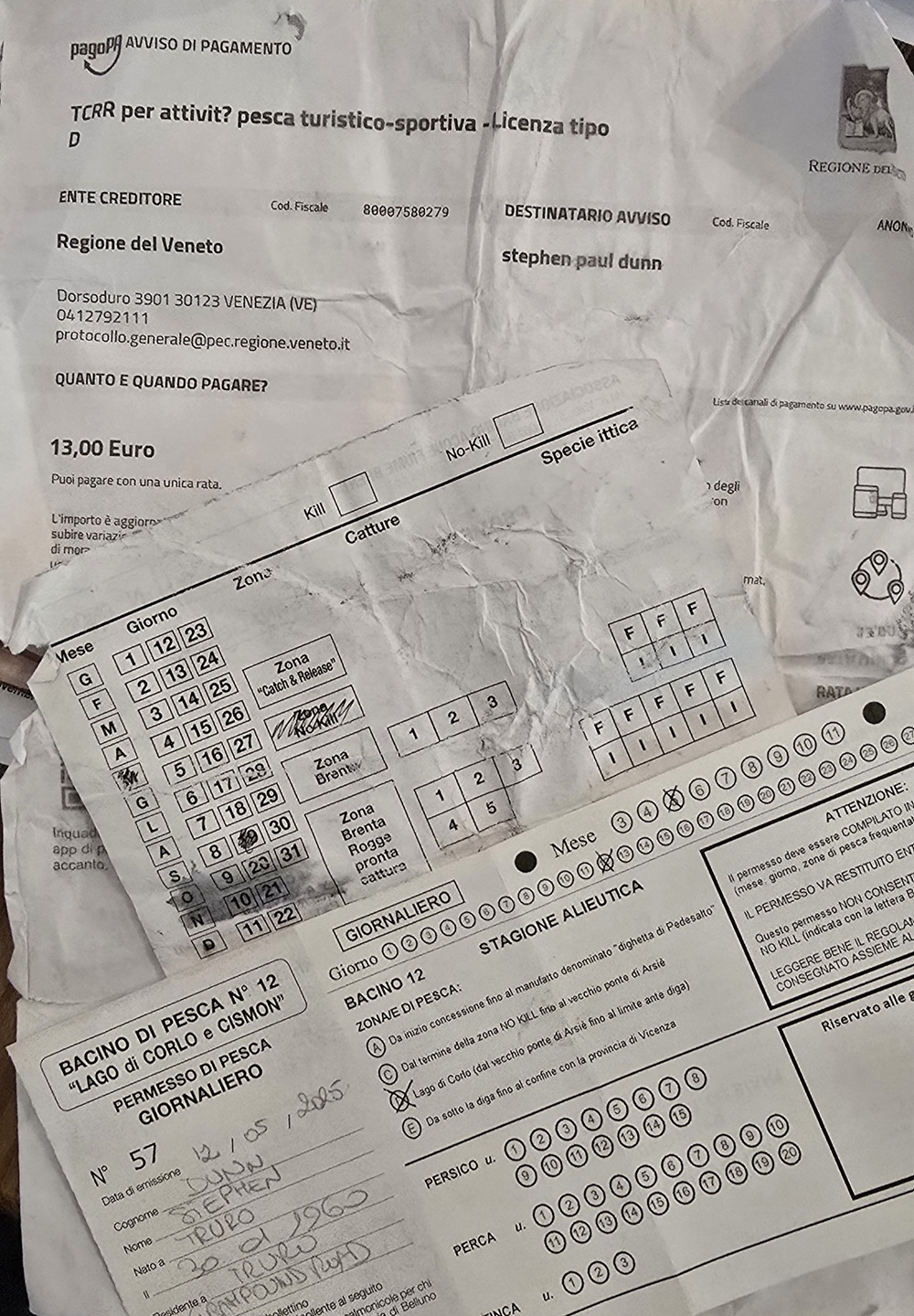

Meanwhile, to describe the licensing, permit and logbook system as complex would be an understatement. It was unfathomable! I eventually gave up trying to get a licence online and accepted that, as far as I could tell, I’d need to fill out a form, attend a post office with two passport photographs (that at least turned out to be a red herring), and then wait an unspecified time to get my licence. Then, I would need to buy permits in the particular area I wanted to fish. The precise mechanism for acquiring permits was still opaque at this point.

Licensing challenges!

Off to Italy

Up the A30 from Cornwall to Bristol airport (all fishing trips in Cornwall start on the A30), a two-hour flight to Venice's Marco Polo airport, and I was buongiorno and ciao’ing my way through passport control and drinking for-real cappuccinos – which as you all know do not have a dusting of chocolate, come in one size only (small) and are only made with whole milk. Go on, ask for skim milk, I dare you!

A rainy first night and a ferry ride through the canals of Venice was pretty amazing, the hire car was collected the following morning (although the electric car I’d booked had to be replaced by a more expensive petrol model because “Sir, there are no charging stations anywhere near Possagno”), and then my wife Kat and I were on our way to the mountains. I should mention that Kat had a bit of Italian horse-riding planned, but had agreed to share the driving, and take some photos.

My strategy for sorting out licences was to go into a tackle shop and ask an expert. With Gabe (who has conversational Italian) as an interpreter, we went to a shop called Pesca Sensa (sensible fishing) near Bassano del Grappa, a city in the region of Veneto, in northern Italy. Italy’s local government structure is divided into 20 Regions and 107 Provinces. Trout fishery regulation is set at provincial level. Of course, not all 107 Italian provinces have trout fisheries: trout are less common in the warmer and drier south.

The tackle shop was a breakthrough. Luca Carriera, who spoke no English, but judging by the many pictures adorning his noticeboard seemed to be a big game fisherman, spent the better part of an hour organising (through hand signals and guesswork) a €13 Euro Pesca Turistico-Sportiva-Licenzo tippo (a standard tourist fishing licence), and three €20 Daily Fishing Permits. I am reasonably certain I was also required to have a logbook, but either I somehow lost it amongst the small mountain of paper I walked away with, or… well I don’t really know, but I was going fishing anyway!

Brenta River

Gabe took us to Bassano del Grappa to see the Brenta River. A lot of the towns in the region were renamed with ‘del Grappa’ as a suffix after World War 1 in memory of the heavy losses suffered on Mount Grappa. Ernest Hemmingway was posted here as an ambulance driver and lived there after the war. Napoleon stayed here during the 1796 Battle of Bassano where he routed the Austrian forces. I spotted the house he lived in with a small brass plaque as we were walking through a back street to the river. Proper history!

Brenta River

The Brenta River was massive. We stood on a bridge in town which, during the war, had been a strategic location with opposing forces on either side. The walls of the towering riverside houses were still peppered with bullet holes which cannot be fixed under heritage laws.

Looking 25 metres down to the river, I had one of those, ‘How the hell am I going to fish this?’ moments, mentally calculating the volume of water passing under the bridge… 100 metres wide, over a metre deep and travelling at a metre a second… That’s getting up towards the Tumut River below Blowering Dam at peak flow and threatening to break its banks. The water was a milky colour, which just added to the challenges. Did I remember to pack my split shot? Maybe I could dredge up a few bullets or musket balls from the river!

Still, I wasn’t deterred. The brain is a funny thing: it chews big problems over subconsciously day and night while you go about your regular business, and nudges you to do stuff. Late that evening, I got onto to Maps and followed the course of the Brenta River upstream, noting that the main road tracked it all the way. I spotted a tributary entering the river about 25 kilometres upstream, at Cismon del Grappa, called the Cismon Torrent. Two days later, licence and permits in hand, we set off. (I should mention that before you start to fish, the permit has to be validated with details filled in of the date, and zone-type you are fishing – for example, catch-and-release.)

As we made our way into the mountains, it became clear the road tracked the river because the river follows a deep gorge with towering cliff faces on either side. At times the distance between the two cliffs appears to be no more than a few hundred metres. For most of the way, there is a road on both sides of the river – one a highway, the other a minor road that often narrows to a single lane through the many small villages and towns along the way. There are several narrow bridges joining the two roads, and both roads are supported in many places by high rock retaining walls.

It’s hard to concentrate on driving when you’re constantly staring at the river. At a number of promising spots I tried to find river access, but parking was very difficult, and a lot of the river adjoined private property. Add to that, the rock embankments were very overgrown and often 5 metres or more in height, and near vertical in places. By the time I reached the Cismon, I hadn’t found one sensible access point at a fishable spot.

Cismon introduction and a lake detour

However, as soon as I saw the stretch where the Cismon Torrent joined the Brenta River at Cismon, I knew it was a good call. It reminded me of the lower stretches of the Eucumbene River just above the tree-line on a good-flow day. The water was gin-clear and looked amazing, with bouldery runs, deep pools and long glides.

It was around 8.30am and still three-layer chilly. I parked near the town and walked out onto the bridge. From eight metres up it looked as fishy as hell! I could still see no public access points, although there was a track (game trail?) of sorts among the vegetation by the river. I gave it an hour driving up and down, and found nothing other than a small parking area by an electricity substation. I did think about stopping there but the signs and the CCTV (not common in these parts) looked a bit serious.

Still undeterred, I headed over the bridge and ended up back on the highway, following my nose. The road swung left so I exited the main road, expecting the sweeping turn to lead me back south but ended up in a tunnel under the mountain! It was an impressive tunnel, over three kilometres long, and I was heading northeast. As soon as I got out, I took a right turn with the aim of heading back, but spotted a lake on the map, Lago del Corlo, about 3 kilometres long and a bit under a kilometre across at its widest. How simple a bit of lake fishing seemed right now, so I followed the signs for the Lago del Arsie camping village – the name of which seemed childishly humorous. Here I found cappuccino and a pastry, and relaxed. (Driving in Italy is a little bit stressful!) And they sold permits for lake fishing at the reception. Goodwill however did not extend to access to the campsite foreshore, so off we went again. The lake shore was heavily overgrown but there were plenty of stretches that looked promising.

It certainly isn’t a lake where you can walk for miles along the banks, but soon enough I’d parked and got my gear sorted, quickly losing a few flies in the dense foliage in every direction, but buoyed by the odd large dark shadow cruising past just a few metres offshore. I tried everything but, in the end, I decided to move. A large swirl in the water I’d stirred up whilst getting out of the water almost had me going back in.

After the raging rivers, a genteel lake enviroment was appealing.

We drove back towards the campsite and found another spot with a few less trees and very deep water, right off the bank. A good rise within castable distance got me excited and I tied on small nondescript foam fly with rubber legs, calling to me from the fly box. A few casts and nothing else, but then the deepwater wraiths appeared again. What was I looking at? Schools of three or four fish, swimming together, then one breaking off having seen something to eat perhaps? Rejoining and then disappearing. The lake was quite clear, though with a milky-green tinge from snowmelt which prevented me from getting a definitive look. Again, another hour and nothing, but then, a rise, quickly covered by the Stimulator I had tied on in desperation.

It promptly disappeared, and I lifted into a solid fish which stripped off line during its first dash, and kept me busy for five minutes or so before eventually coming into the shallows. “It’s a bloody carp!” I shouted to Kat. Well, carp-like. But to be honest, I was thrilled to get a run on the board, and it was a beautiful-looking fish in its native and attractive environment.

A fish at least, and on the dry.

I didn’t get a trout that day but it didn’t matter. I knew I had to rethink my strategy, and as we drove back through the tunnel and along the narrow winding roads towards Possagno, I decided I needed to get some expert advice.

The next few days were spent with Kat doing horse work. We were near the other major river in the region, the Piave, and I tried, frustratingly and unsuccessfully, to find a local guide. The Piave is immense and I wouldn’t even try to fish it without help. It seemed to be several times larger than the Brenta, and when the water level dropped later in the trip, it braided through boulders across hundreds of metres of riverbed. I did go and investigate below a large weir and it looked like something from Iceland! But with each permit costing nearly $50 a day, you can’t just get your gear out and do 5 minutes of prospecting.

The enormous Piave River.

If I was going to catch Italian trout, it looked like I’d need to come up with a different approach...