Know the rules and the rules of civility when it comes to freshwater angler access. (Moorabool Reservoir - pic courtesy VFA)

I was approaching the water – a small creek that ran through a drain under the road – stripping line from my reel and two or three false casts in when I heard someone yell at me from across the street.

“What do you think you’re doing?” He sounded angry. “It’s a private waterway, mate, you can’t fish here.”

I’d seen a nice rainbow trout just ahead of the drain that took the creek under the road and into his property, and had taken it upon myself to catch it.

I was targeting about a square foot of water upstream of the concrete 500mm pipe.

In truth I’d seen about three rainbow trout between his fence and the properties across the road upstream. I’d had a cast at a smaller one in the morning from his nature strip.

That little trout had had a look at the fly, but possibly the offering was too big or the tippet too heavy to ignite the required interest. And to be honest, the cast also wasn’t quite up to scratch, landing below the fish. Anyway, sensing something was off, the fish swam into the cover of the drainpipe.

Nature strip trout.

The better trout seemed to be on the upstream side. I’d seen it take something at the edge of the creek, basically in the road verge. I said as much to the angry homeowner.

“Yeah, there’s always rainbows in there and I’d like to keep it that way.”

“I would’ve released if I caught it,” I said, taken aback.

I wound in, having only landed the fly on the grass. I got back in the car, a bit shaken by the encounter.

The year I saw the fish in the drain was at the tail end of the three wet years at the start of this decade and there were trout everywhere.

When I spotted the bigger one in the drain, the tell-tale pink stripe on its side glistened in the sunlight, while its movement momentarily added some fine grey silt to the shallow clear water it was feeding in.

Seeing fish like this had put me in the mood to catch one from water that looked unlikely to hold them, so I drove down the road to another very small creek which passed under the road through another drain.

I pulled into a small picnic area by the creek, confident I wouldn’t be accosted by any angry landowners who felt the trout were their pets.

It was a dry fly time of year and day. I navigated creek-side branches and grasses as I cast and drifted a Tabanas into the micro drop-offs where the creek’s riffles spilled into tiny pools. It was generally easier to cast downstream and mend the line to achieve a short natural drift.

In a few casts I hooked what can only be described as two ridiculously large rainbows for the water. One would have gone 30 centimetres from a bit of water not much wider or deeper than it was.

My faith in the divine experience of life was restored, although somewhere, the bad feeling from the encounter with the landowner lingered. I wasn’t convinced I was in the wrong trying to catch the fish in the drain, but I wasn’t really in the mood to come to verbal or physical blows over my right or otherwise to fish it.

Much better to get the lawyers involved.

Seeking clarity

After the trip, I spoke to a friend who is experienced in property law. His review of the state government’s Land and Spatial Survey Information website showed the property boundary ending at the nature strip, meaning the little patch of creek I was targeting between the property fence and the road, and that the rainbow trout was enjoying, was flowing on publicly-accessible council land.

When my lawyer-friend looked on Google Earth, via satellite and then from street view, he said, “What? That’s a creek? There were trout in there? It looks like a puddle.” Once he got over his surprise he said, “You’re within your rights to fish it. So until you get arrested or the abuse becomes too much, that’s the advice for now.”

Take that angry homeowner, I thought, or maybe not. Being abused for trying to catch a fish from a virtual stormwater drain didn’t seem worth it.

It was a good lesson either way on the need to be armed with the correct information and the willingness to stand your ground when you’re in the right.

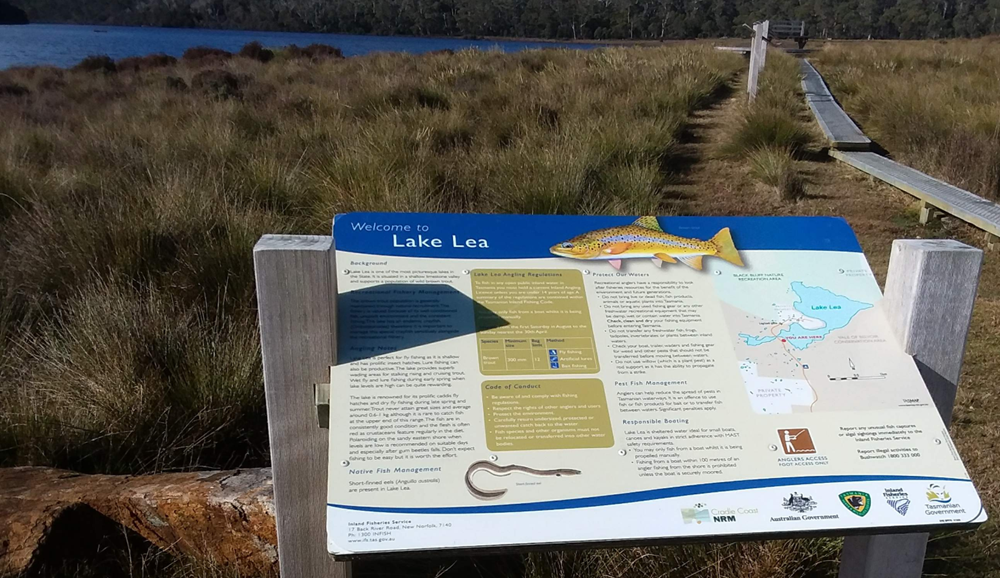

No ambiguity here!

My general sense was that I could fish rivers and creeks flowing through public land (except maybe in certain protected drinking water catchments), particularly if accessing it from a bridge or road crossing. At the same time, seeking the permission of any landowner whose property I had to cross to get to a stream, was also the right thing to do.

It turns out that understanding pretty much stacks up in Victoria when it comes to larger waterways with licenced or unreserved Crown land frontages (leased Crown land frontages are different), particularly when angler access signage is installed and helpful landowners and government bodies have installed stiles to make getting over fences easier. However, some smaller creeks on titled land fall into the private waterway bracket and so I wasn’t within my rights to jump the angry homeowner’s neighbour's fence and start fishing upstream through his backyard.

Then there’s the situation where rivers change course and the titles don’t keep up, so fishing a river that once flowed through Crown land but now runs through private property, can create conundrums and points of conflict for those seeking to fish. This highlights that, in Victoria, access really boils down to the land titles in most cases.

While there's still angler access in parts, The Breakaway on Victoria's Goulburn is a classic example of a river changing course and leaving its Crown frontage behind.

In New South Wales, land titles will often extend into the middle of rivers. In that state, the land under the water is owned by the landowner in these instances, so to be even standing in the bed of the stream fishing means you could be considered to be trespassing. That is until you wade into section 38 of the state’s Fisheries Management Act 1994, the first clause of which proclaims: “A person may take fish from waters in a river or creek that are not subject to tidal influence despite the fact that the bed of those waters is not Crown land if, for the purpose of taking those fish, the person is in a boat on those waters or is on the bed of the river or creek”.

There might be a catch though in clause 2: “The right conferred by this section is subject to the other provisions of this Act.” Further reading required.

Tasmania has similar titles along many rivers, and the state’s Inland Fisheries Service has worked to create formal access agreements with landowners in many places for the benefit of the state’s local and visiting anglers.

Angler access point near the Meander River in Tasmania. (pic. courtesy of IFS)

Encounters like the one I had at the start of this story are not uncommon, regardless of what the rules stipulate. So as well as knowing the rules, knowing the rules of civility are equally, if not more, important. Both New South Wales (via the Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development), and Tasmania (via the Inland Fisheries Service), have codes of conduct and guidance on that front.

Drinking water catchments and storages

One place where the rules of civility don’t make much of a difference, is fishing in protected drinking water catchments.

Even if you ask nicely, the water corporation often won’t let you fish there.

When I got a job in communications at a water corporation, I asked one of the catchment managers why people couldn’t fish in the catchment or wade into the lakes they stocked with trout. She said that, “As long as they don’t put their bum holes in it, it would probably be all right”.

Aside from feeling the need to get wording to that effect on some signage at the reservoirs, I did wonder rhetorically why every other animal in the catchment had the right to put its bottom in the water.

Of course, in the days of PFAS and other emerging contaminant monitoring, it’s more complicated than that, so I understand why water corporations don’t want people fishing in protected catchments

I mentioned access to protected drinking water catchments to a friend who worked in the water industry for another water corporation in Melbourne. She described how once, when she was touring a catchment area with a group of fellow employees as part of her work, a fisherman walked into their midst and, much like Abe Simpson entering La Maison Derriere and seeing Bart on reception, promptly picked up his hat and turned and walked out again, whistling all the way.

We know what we’re doing.

Returning to the stormwater drain this year armed with the knowledge of my right to fish it, didn’t mean I was going to (it also didn’t mean I wasn’t going to).

It was a bit of a moot point when I arrived, as the trout were no longer in that section of the creek. This wasn’t unexpected, with numbers down on the previous boom years. I didn’t see the landowner and wondered if he was inside his house mourning the loss of his fish.

Many people were blaming cormorants for the decline in fish numbers, but camping by another tributary creek a touch further up the valley I saw another possible culprit one morning when I was watching the water.

It turned out to be a rakali (a water rat), whose brethren I had seen catching trout at other times. It was actively moving in and out of undercut banks as it variously swam and crawled upstream. I was curious about where it might lead and what it might show, so I followed it upstream for a hundred metres or so.

Hungry rakali.

In a pool that was big for the creek but small by any other measure, the rakali spent more time vigorously swimming in and out of a submerged tree branch and undercut bank. To my mind, it was trying to unearth any little rainbow trout that might be hiding there, and/or other aquatic life that called the creek home.

Unfortunately for it and me, its movements didn’t reveal any fish, or none that it caught. Tough times for all.

As I watched it, it occurred to me that while I thought the drain might have stopped the cormorants, it could have merely served as a buffet for the rakali.

The creek might have also dried out over the summer months; although maybe the landowner’s love of his fish would have seen him cart some water in to maintain the flow.

When the trout are everywhere like they were a year or two ago, we want to catch them everywhere. Even when they’re not everywhere, we still want to have a go; and when we’re not allowed to, yet feel we should be allowed to, it can create some issues.

Good conduct

As anglers, we want as much water to fish as possible and to fish it in a way that supports local communities and respects landowners, but the rules need to be respected by everyone, not just the fishers.

Angler access isn't all about private versus public - there's also the issue of abiding by local rules and codes of conduct. (pic. courtesy of IFS)

New South Wales and Tasmanian government bodies provide information online about angler access points on many lakes and streams, and work being done to improve and expand them. In Victoria, catchment management authorities like North East Catchment Management Authority have resources to aid with understanding access rights, while organisations like VRFish and the Australian Trout Foundation and even the Victorian Fisheries Authority itself, are advocating to ensure existing rights of access are upheld.

Regardless of whether it’s Crown land or not, it’s probably best to treat access to any waterway as a privilege and not a right – but know your rights all the same. Until you get arrested or abused, that’s the advice for now!