There’s a bit of a push on at the moment to stock some trout streams that normally rely on natural recruitment. But is stocking these wild trout streams the best management option?

A Bit of History

Started by multiple lightning strikes on 8 January 2003, the Alpine Fires burned millions of hectares of the mainland’s best wild trout country before they were finally contained nearly 2 months later. It was no surprise when 12 months on, a respected senior journalist, writing in a major newspaper, declared ‘the reality is, trout fishing in Victoria is in steady decline.’ The article laid much of the blame for this decline on a Fisheries’ reluctance to stock streams. Probably in the interests of balance, I was named as a ‘noted’ angler who believed stocking wouldn’t have improved the state the streams were in.

I count the journalist in question as a friend, and I didn’t begrudge him putting it out there that I held this unpopular view. He was quoting me more-or-less correctly (there are some streams that definitely need stocking, but most don’t.) I could understand the fear many anglers held that the trout could never recover on their own from the 2003 cataclysm. After all, on my bookshelf I had a bottle of water that I took from the Indi River following one of the post-fire ash runoff events. The water was so black you couldn’t see through the bottle to the other side. How could anything, let alone a trout, recover from that?

Frightening times on Australia Day Weekend 2003 as smoke clouds tower 10,000 metres above the Indi valley.

Frightening times on Australia Day Weekend 2003 as smoke clouds tower 10,000 metres above the Indi valley.Some Evidence

In my gut I doubted, but intellectually I knew the wild trout would recover from the fires all on their own. I’d seen the same miracle happen, albeit on a smaller scale, many times before. So it proved. By the time that newspaper article appeared I was already enjoying good fishing on several fire affected streams. Here are some abbreviated diary entries from that time:

10/2/04 Mitta Mitta (Big) River – Glen Valley.

Cloudy, few spots of rain. Air temp. 26 C, water temp 16.5 C. Fished with NSW Fisheries’ Al McBurnie 11 am – 6.30 pm. Self: 12 browns between ¾ - 1½ lb. (Al’s catch not recorded)

11/2/04 Rocky Valley Branch of East Kiewa River

Cloudy, few spots of rain. Air temp. 25 C, water temp 16.5 C. Quick fish with Jane 2 -2.30 pm. Self: 3 rainbows ¾ - 1 lb.

15/3/04 Nariel Creek – Nankervis Bridge.

Sunny. Air temp. 28 C, water temp 18 C.

Fished on my own 12 - 2 pm; 12 browns & rainbows, ½ - 1¼ lb.

15/3/04 Indi River – Biggara.

Sunny. Air temp. 25 C, water temp 19 C. Fished on my own 2.30 - 4 pm; 10 browns & rainbows, ½ - ¾ lb.

None of these streams had been stocked since the fires; the remarkable recovery occurred purely through natural recruitment. Fisheries did stock 1,300 fin-clipped brown trout into the mudslide-devastated Buckland River in late 2004. Yet my friends and I failed to find any of these fin-clipped Buckland browns, despite catching plenty of wild trout in this river through 2005/2006.

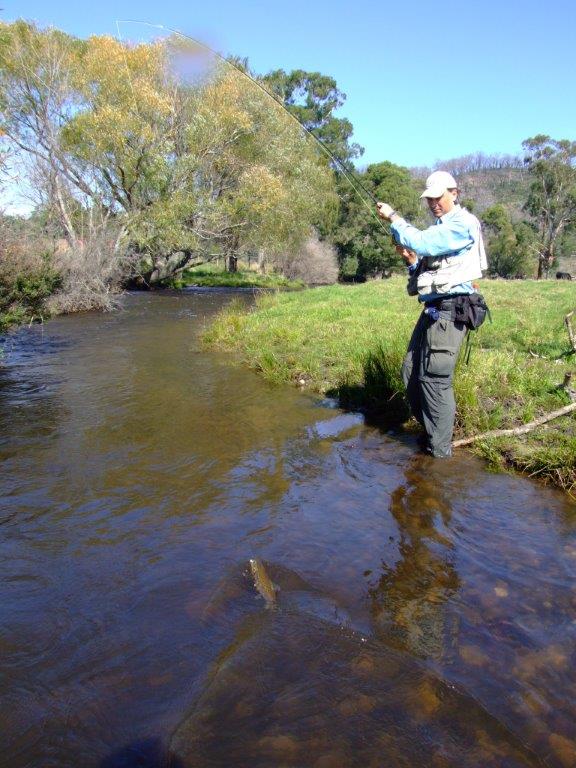

The Steavenson River was devastated by the 2009 Black Saturday fires, but just 12 months later it was producing great fishing again for naturally-recruited trout.

The Steavenson River was devastated by the 2009 Black Saturday fires, but just 12 months later it was producing great fishing again for naturally-recruited trout.The Science

Numerous scientific studies here and abroad have proved that, in given a river system with a history of successful natural recruitment, a few surviving trout somewhere in that system are enough to quickly replenish the stocks. Once trout habitat recovers (and no trout – stocked or otherwise – can survive without food, cover and clean water) the offspring of the survivors rapidly recolonise. As one fisheries scientist simply puts it, “Trout don’t like a vacuum.”

Evidence that questions the value of stocking wild trout fisheries has been around for a while. Dr Aubrey Nicholls’ research during the mid-1950s on Tasmania’s St Patricks and North Esk rivers demonstrated that the stocking of tens of thousands of trout made no significant contribution to natural stocks; a point confirmed by further IFC research on the same waters 30 years later.

Meanwhile, research in Montana during the1960s was suggesting that stocking wild fisheries wasn’t merely a waste of money; it was harmful. In his book ‘The Living River’ (Winchester Press, 1979) Charles E Brookes recounts how a comprehensive study of the famous Madison River found that when stocking hatchery ‘catchables’ (15 cm plus; about the same size as Snobs Ck yearlings) ceased on one section of the Madison in 1968, by 1969 the number of wild trout of this size had quadrupled. More disturbingly, when hatchery catchables were stocked into another section of river that hadn’t been stocked for years, the overall population of trout of this size actually halved.

The extensively-studied Madison River in Montana has taught us a lot about how to best manage wild trout fisheries.

The extensively-studied Madison River in Montana has taught us a lot about how to best manage wild trout fisheries.This last observation raises something more worrying. In the Science section of The New York Times (13/7/1991) behavioural ecologist Dr Robert A Bachman described how hatchery trout, suddenly thrust into the stable social order of wild trout, create confusion and chaos. Bachman found that the result was ‘fewer fish of either kind.’ The Times article concluded that ‘Other studies have also found that stocking tends to reduce the number of wild trout. The hatchery trout dwindle too, since they are generally more easily caught and less adept at feeding…The outcome is often an impoverished fishery…’

By 2010, my personal experience watching numerous trout fisheries recover from fire and drought had persuaded me that stocking wild trout fisheries was usually folly. However, I believed there was an exception in the case of the King River below Lake William Hovell. This artificially-regulated river often experiences a dramatic post-irrigation season drop in level – just as the browns are beginning to spawn. At the same time, the dam itself blocks access to the ideal spawning creeks above it. Therefore, I was supportive of a plan to stock the river for 2 years with a total of 5000 fin-clipped trout – I felt sure that in this unusual case, the stocking would benefit the fishery.

But I was wrong. My friends and I – all supportive of the stocking program – caught scores of King River brown trout through 2010, 2011 and 2012, including some beauties. However to our surprise, not even one was a fin-clipped stocked fish.

How do they do it?

I’ve been unable to find a single fisheries scientist anywhere who supports stocking wild, self-sustaining trout fisheries, and I guess that now comes as no surprise. To simplify a little, wild trout recovery works like this. Every year, wild trout lay millions of eggs in the suitable gravel of their home river systems. Perhaps ironically, following a ‘good’ year for overall trout survival – one without things like fires or drought or excessive attack from cormorants – the vast majority of these eggs and their subsequent hatchlings perish; there is too much competition and predation from older trout. For example, in many rivers, the prime spawning beds are repeatedly dug up by successive breeding pairs and the eggs of earlier spawners are swept downstream and lost. Only the later spawners actually succeed in having their eggs survive until hatching.

But the reverse is true following a ‘bad’ trout year. Although the total production of eggs is much lower, the proportional survival rate of eggs and fry is much higher. These young trout then have the run of the river, with limited harassment and predation from older fish. They grow incredibly quickly too with all the food to themselves, and in another endearing trout trait, many of the young fish are programmed to wander and soon recolonise any suitable stretches or tributaries that are vacant. I know of several small streams in north-east Victoria that were bone dry for months almost every year during the 2000s, but which subsequently held three pounders after only a couple of seasons of good rain. There was no help from stocking – the trout found their way all on their own once conditions were suitable.

Stocking IS vital…sometimes

After all that, it may be a surprise to hear that I am rabidly pro-stocking when it comes to many trout waters across south-eastern Australia. For example, virtually all the great trout lakes in western Victoria, and many rivers in the same area, would soon cease to contain trout without regular decent stocking – facilities for natural spawning are either limited or non-existent. The same applies to many New South Wales waters. It’s critical that we maintain strong Government-controlled hatcheries in both States, focused on producing salmonids of high quality, as well as in sufficient quantity.

Stocking isn't intrinsically good or bad, it's simply appropriate for some waters and not others. This is a lovely stocked brown trout from Lake Fyans in western Victoria.

Stocking isn't intrinsically good or bad, it's simply appropriate for some waters and not others. This is a lovely stocked brown trout from Lake Fyans in western Victoria.But it’s equally important that we accept stocking of viable wild fisheries is, by and large, no solution to their recovery or improvement. What seems at first glance like a logical fix to poor fishing or perceived poor fishing – adding more fish – turns out at best to be a waste of money, and at worst actually detrimental.

Other Options

We are certainly far from powerless to improve wild trout fisheries that are performing below their best. While the evidence fails to support stocking as a solution, it emphatically shows the benefits of habitat improvement, and fishing regulations that sensibly manage the angler take of wild trout. So there is plenty anglers can do and advocate for that will help affected wild trout waters recover, and then retain the healthiest possible condition within the constraints nature imposes. There are streams in the USA where the trout population has been increased 10-fold solely by improving physical habitat. Now that’s food for thought!